On that Day, Every Knee Shall Bend (2)

And behold, a pale horse. And the name of him who sat on it was Claude

The he showed me the river of the water of life, bright as crystal, flowing from the throne of God and of the Lamb through the middle of the street of the city; also on either side of the river, the tree of life with its twelve kinds of fruit, yielding its fruit each month; and the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.

Revelation 22:1-2

[The mahdi] will offer something that no one has ever offered before him. He will fill the world with justice, equity and light after it has been filled with injustice, oppression and evil.

al-Nu’mani, Kitab al-Ghayba (The Book of the Occultation)1

In my last post I approached the question of computers and the Internet from the perspective of media theorists such as Neil Postman, and while this will be important to the question of how we think about the tools currently being called “AI,” I’d also like to also think about some of the world-historical claims being made by the proponents of these systems. Admittedly, this is taking the bait of the current AI hype cycle — guilty as charged. However, there is serious money being poured into these tools by serious funders, and the founders and executives of these companies are making serious claims, and so we should examine what they are saying seriously without waving them away as another bubble driven by equal parts collective mania and the profit motive.2

Before getting too deeply into my own read on the matter, it will be useful to consider two recent visions for AI-mediated society. One is quite short: The Intelligence Age from Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI, which is, to be generous, a broad overview of AI ideology. It is, however, largely in lockstep in its approach to how AI is likely to influence human society as the CEO and co-founder of Anthropic Dario Amodei’s slightly more comprehensive Machines of Loving Grace.3 Both of these certainly have a vision for the future, and whether that vision is more related to long-term investments towards technological development or John of Patmos will be up to the reader to decide.

They shall flourish as a garden; they shall blossom as the vine

To begin with Altman, there is less exegesis to be done because The Intelligence Age reads to me as, rhetorically, meant to inspire those already working in the field as much as it is to lay out what AI will “mean” for society. For example, apparently without irony, one can read that “in the future, everyone’s lives can be better than anyone’s life is now,” that “the story of progress will continue,” and that the development of AI “may turn out to be the most consequential fact about all of history, so far.” But rather than try to draw out some of the assumptions being carried here — I believe these are also meant to provoke AI skeptics, not convince them, and thus drive a cycle of reaction which is key to our “attention economy,” as it were4 — I think it may be more useful to look at the understanding of history on display, and the tangible results being promised.

The basic historiographical method is a progressive model in which the prime divider of human eras is technological development, so in place of Ancient-Medieval-Modern, we have Stone Age-Agricultural Age-Industrial Age-Intelligence Age. The repeated mantra is that technology allows humanity to “solve hard problems,”5 and while there is a token acknowledgment that there are certain tradeoffs — the Intelligence Age is admitted to likely not be “entirely positive,” and there will, yes, be “a significant change in labor markets” — these are outweighed by the “enormous benefits” which can be reaped by allowing humanity to “amplify our own abilities like never before.” The reason this can all happen is, proving the relevance of Neil Postman from Part 1, that “humanity discovered an algorithm that could really, truly learn any distribution of data.” The ultimate manifestation, then, of the internal logic of computer-as-medium.

This may seem a little light on details, but in fairness, Altman does nod to some of the “hard problems” that will allegedly be solved by AI:

Virtual tutors for children, with “similar ideas” being used in healthcare (which is already happening, in a certain manner of speaking)

“Autonomous personal assistants who carry out specific tasks on our behalf like coordinating medical care on your behalf [sic]”

“Fixing the climate”

“Establishing a space colony”

“The discovery of all physics”

There is a curious part in the conclusion of this piece which comes alongside all of this increasingly ecstatic expectation for the triumph of AI, in which Altman imagines the mindset of our predecessors in humanity:

Many of the jobs we do today would have looked like trifling wastes of time to people a few hundred years ago, but nobody is looking back at the past, wishing they were a lamplighter. If a lamplighter could see the world today, he would think the prosperity all around him was unimaginable. And if we could fast-forward a hundred years from today, the prosperity all around us would feel just as unimaginable.

This strikes me as a classic misstep in historical thinking, which is that people in the past were epistemically stunted by virtue of lacking our technological conveniences. But note the use of the adjective: unimaginable. It is being used here to suggest that it is the prosperity from technological development that cannot be conceived, but I have to wonder — if, taking this frame seriously, we cannot properly imagine the world a hundred years on from AI, why did we just read an essay full of tangible, imaginable results that can be expected? This would be of concern in a less progressive historiographical approach, but as is, it is taken to be a mental block concealing only more wonders to come.

To turn to Machines of Loving Grace, Amodei’s piece is quite a bit more substantial than Altman’s short post, but it is largely speaking the same language and working with the same assumptions about the rhythms of history. While opening with the caveat that the author himself “think[s] and talk[s] a lot about the risks of powerful AI,” the reader is meant for this to be wholly overpowered by the thesis of the work as a whole: “most people are underestimating just how radical the upside of AI could be, just as…most people are underestimating how bad the risks could be” [Note: the bold formatting is from the original].

The conceit at the heart of Amodei’s piece is that a sufficiently powerful AI — a “pure intelligence” that can not only “passively answer questions” but can “work autonomously” on increasingly complex tasks, possibly in coordination with other pure intelligences to maximize efficiency — is the equivalent of a “country of geniuses in a data center.” Each of these tools is, to wit:

…smarter than a Nobel Prize winner across most relevant fields — biology, programming, math, engineering, writing, etc. This means it can prove unsolved mathematical theorems, write extremely good novels,6 write difficult codebases from scratch.

Where Amodei’s piece is more compelling than Altman’s is not only in its recognition of potential limitations to AI development — for example, the physical laws of the universe, or the human tendency to be “inefficient” — but more detailed examples of the sorts of “very difficult problems” that AI tools will be able to solve. These fall into five basic categories:

Biology and physical health

Neuroscience and mental health

Economic development and poverty

Peace and governance

Work and meaning

While I am most interested in thinking about points 4 and 5, in the interest of fairness, scientific research may well be the area where AI tools have the greatest promise by virtue of their ability to rapidly process data and detect patterns that otherwise would take hours/months/years of human effort. If we take Amodei at his word — that he believes that his “country of geniuses” will be able to complete scientific research at 10x the usual speed, and what would usually take 50-100 years of work will be completed in 5-10 — biological advancements which ease human suffering are difficult to argue with per se.7 What is being promised in these first two sections is no less than the elimination of nearly all infectious disease, most cancers, improved treatments for genetic diseases, the cure and prevention of “most” mental illnesses, and generally a completely new paradigm for medicine and wellness. If that is not sufficiently rosy, Amodei also muses that “once [the] human lifespan is 150,” rapid technological advancements may (though there is “no guarantee”) mean that some humans currently living “will be able to live as long as they want.” I will let the biologists/chemists/psychiatrists go in and do the line-by-line consideration of whether what is being promised is remotely feasible, but I am really more interested here in the world-historical vision of a human experience free from the shackles of disease and death, which is to say, Nature.

I’m going to jump to points 4 and 5, both because I think they are revealing of how Amodei imagines AI to function with regard to human society as opposed to processing and directing lab research, and because the third section (as the author admits) is a little fuzzier on the specifics.8

The section on “Peace and governance” opens with a refreshing caveat that AI tools are as likely to “enable much better propaganda and surveillance” as they are to encourage peaceful and prosperous democracies. As the essay is working from a premise of inevitability, the recommended response is not to cease inherently-invasive AI technologies, but to ensure they are managed by a “coalition of democracies.” So, on a world scale, the vision is of an “Atoms for Peace” program that instead bestows or restricts access to “the benefits [sic?] of powerful AI” based on various nations’ promotion of democratic governance. As, in this formulation, AI being controlled by liberal democracies necessarily leads to the free-flowing of accurate information, and as “there is a good chance free information really does undermine authoritarianism,” then it follows that “if we design and build AI in the right way,” it will be a boon for “advocates of freedom.”

And if AI is accurate, impartial, and as close to omniscient as its training models will allow, then why not incorporate it into domestic legal systems due to its “combination of impartiality [and] ability to process messy, real world situations” as an aid to human judges? There are a few other fuzzy predictions, such as AI being used to “both aggregate opinions and drive consensus among citizens, resolv[e] conflict, [find] common common ground, and [seek] compromise,” or serve as an assistant “whose job is to give you everything you’re legally entitled to by the government in a way you can understand — and who also helps you comply with often confusing government rules.” There is a discussion to be had about whether this seems remotely feasible, but I will just note the underlying theme that the way to solve problems with human society (some might say human nature) is to increasingly reduce the amount of human control over knowledge production and decision-making. Some might consider this a curious definition of justice and democracy.

The final section on “work and meaning” is, by the admission of the author, “more difficult than the others,” but it is also one of the most revealing for its vision of human history, or what might be better described as post-historical humanity. The author imagines himself receiving two follow-up questions to his vision of AI-mediated life: “with AI’s [sic] doing everything, how will humans have meaning? For that matter, how will they survive economically?” I get the sense that the essay is starting to run out of steam a bit, because the second question is largely punted for a future piece, though there are musings about a universal basic income system emerging from “a capitalist economy of AI systems, which then give out resources…to humans based on some secondary economy of what the AI systems make sense to reward in humans (based on some judgment ultimately derived from human values).”9 But there is a very telling paragraph about how meaning is derived that is worth looking at in full:

On the question of meaning, I think it is very likely a mistake to believe that tasks you undertake are meaningless simply because an AI could do them better. Most people are not the best in the world at anything, and it doesn’t seem to bother them particularly much. Of course today they can still contribute through comparative advantage, and may derive meaning from the economic value they produce, but people also greatly enjoy activities that produce no economic value. I spend plenty of time playing video games, swimming, walking around outside, and talking to friends, all of which generates zero economic value. I might spend a day trying to get better at a video game, or faster at biking up a mountain, and it doesn’t really matter to me that someone somewhere is much better at those things. In any case I think meaning comes mostly from human relationships and connection, not from economic labor.

Bracket for a moment the curious framing in which one feels the need to insist that there is, in fact, meaning beyond the production of economic value,10 as well as the load-bearing “better” in the first sentence. While it is hard to argue that human relationships are an important way of generating meaning, notice the seamless shift in the third sentence from the derivation of meaning to the enjoyment of pleasure. Normally I would categorize these as two separate concepts, but the implication of both this sentence and the list of what are mostly hobbies immediately following suggests an AI post-historical moment in which one will have the freedom and security to play video games and go for walks as much as one likes. There is a nod towards the human need for a “sense of accomplishment,” but the author takes what others would have criticized as ultimately-meaningless surrogate activities and defined them as a genuine source of internal meaning:

People do want a sense of accomplishment, even a sense of competition, and in a post-AI world it will be perfectly possible to spend years attempting some very difficult task with a complex strategy, similar to what people do today when they embark on research projects, try to become Hollywood actors, or found companies. The facts that (a) an AI somewhere could in principle do this task better, and (b) this task is no longer an economically rewarded element of a global economy, don’t seem to me to matter very much.

One might note some of the potential sources of meaning that are lacking from this conception: autonomy over one’s own life is the major one, but also responsibilities towards others, or fusty old notions such as “duty” or “honor” which also tend to not generate much “economic value.” It is not technically true that all of these are overlooked entirely, as the conclusion of the piece states without apparent irony that it is “intuitive that people should have autonomy and responsibility over their life choices.” But the tension of this statement with the post-AI society described throughout the piece is not resolved.

To look at these two pieces as a whole: it may have seemed to this point that both the AI manifestos and my commentary were part of a discussion of a new piece of technology and its effects on human society. While that is a conversation worth having, I perceive a different tone driving these. What I believe is actually being discussed is closer to a series of meditations on what will remain after the coming of the messiah.

1000 years of justice

Invoking messianic traditions may feel like a non sequitur in comparison to the discussion of AI in Amodei’s piece in particular, which, admittedly, hedges its bets at certain points and at least nods to physical limitations on the demigod currently under development. One thing that strikes me about AI ideology, though, is less its claims to create paradise on Earth — one can imagine any utopian offering release from disease, fear, and suffering — but the framing of these developments as inevitable. This is a curious thing to say about a project you are actively working on, of course, but the response from a company with an LLM to sell would be, “if we don’t do it, someone else will.” To my (metaphorical) ear, arguing that a world-changing event is inevitable sounds less like we have moved away from discussions of microchips and nuclear power into a discussion of History,11 of Fate, in which certain occurrences are inevitable by virtue of their being part of Destiny. And once you are discussing future events which are destined to occur, you are getting into the realm of metaphysics whether you like it or not.

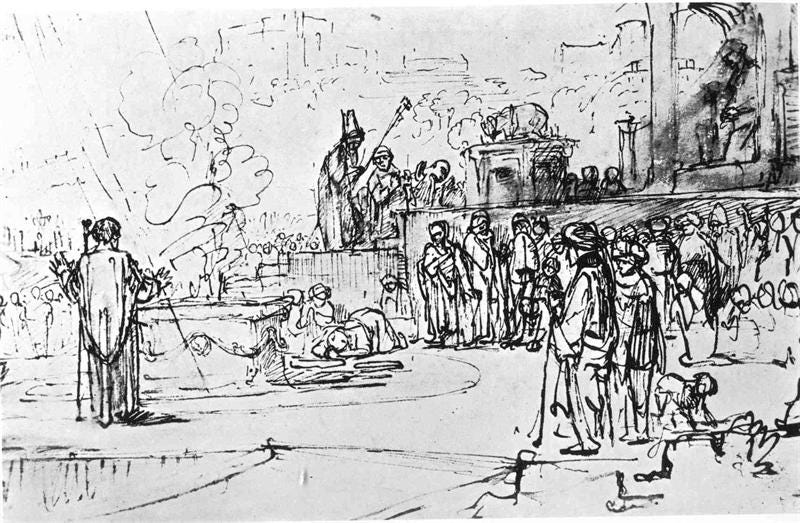

Consider the vision laid out above: the cessation of both physical and mental disease as we know it, the gradual spread of liberal democracy across the entire globe, the prosperity to live a life of peace, leisure, and creativity, and wonders that cannot even yet be defined. Is this really so different from the events of Revelation 20-21? There you have not only the metaphorical exile of the evil principal in Satan but the casting out of Death, the sweeping away of the assembled armies of deception as the kings of the earth walk by the lamplight of Truth, the healing of the nations and a time of justice, with neither “mourning nor crying nor pain.” Does this actually seem like a hysterical comparison given what was discussed above? Unless we are taking the apocalyptic imagery hyper-literally and expecting actual dragons and heavenly cities, can’t each of these be slotted into one of the categories of AI progress above?

Some might bristle at the comparison of AI to Jesus Returned given that what is being described in these AI manifestos is less a literal omnipotent deity so much as a set of created and trained hyper-intelligences. But the idea of the messiah as being non-divine while still the ultimate exegete, interpreter, and revelator of wisdom is an integral part of, for example, the tradition of the mahdi in Islam.12 For the mahdi does not only come to lead his army of 313 companions into battle and victory against the forces of unrighteousness, but to bring true Wisdom (hikma) and the “hidden spiritual meaning[s]” which are otherwise concealed in religious texts. Part of the reason that the mahdi is expected to be able to unite the peoples of the earth behind a single flag and a single religion is by virtue of this ability to revive the inner, esoteric truths of the religious tradition, to shake away the errors of other pathways to reveal the unity behind them — in other words, to persuade through higher-level understanding.13 The mahdi is also able to “solve really hard problems,” such as employing the science of the letters to reveal esoteric realities, or know the true Hebrew name of God. And just as a series of AIs may work iteratively, there are traditions of a series of multiple mahdis.

Of course, every messiah has his antagonists — his Gog and Magog who besiege the camp of the saints, his Dajjal, the masses who unthinkably reject the era of serenity he has to offer — and in the case of deliverance via AI, these fall into what Amodei has described as the “opt-out problem.” These are those who are not sold on “AI-enabled benefits (similar to the anti-vaccine movement, or Luddite movements more generally),” who may be “the people least able to make good decisions” in the first place, and who, as a result, risk becoming a “dystopian underclass.” While the author insists that adoption of AI ought not occur via coercion but rather by “increas[ing] people’s scientific understanding,” and he is sure that as with most “anti-technology movements” opt-outers will be “more bark than bite,”14 there will be real-world consequences to even late adopters whose skepticism leads them to delay connecting themselves into an AI-mediated world:

It won’t be a perfect world, and those who are behind won’t fully catch up, at least not in the first few years. But with strong efforts on our part, we may be able to get things moving in the right direction — and fast.

This is preferable to being cast into the lake of fire or being swallowed up by the Earth when confronting the mahdi, but I sense an ominous tone in some of this loaded language. AI is inevitable; its benefits and eventual adoption are self-evident; resisting its blessings will be to your own harm.

Bracketing the cynical fact that the AI tools such as the one Amodei is building and selling as a product benefit from training on additional human-generated material and, as such, would be harmed by the “opt-out problem,” why is it a problem? The comparison with vaccines strikes me as faulty: the argument for getting a measles vaccine is as much to avoid spreading measles to children as it is to avoid getting it yourself. Writing my own emails or reading articles instead of having them poorly summarized doesn’t harm anyone else’s not-writing and not-reading. But recall from Part 1 the imperative of connection that, I feel, is core to computing technologies: hesitation in this case is not only to separate oneself from society but to deprive AI tools — which in this imagined future are curing disease and ushering in a time of peace and leisure — of the training corpus required to bring such advancements into fruition. It is to reject the Pneuma, to overturn the consensus of the Community, to not only deny the undeniable but attempt to deny it for others. And for this reason, it is necessarily in opposition to the New Jerusalem being imagined above.

Messiahs can be finicky about arriving, though. Ask any Millerite.

فيعطي شيئاً لم يعطه أحد كان قبله، ويملأ الأرض عدلاً وقسطاً ونوراً كما ملئت ظلماً وجوراً وشراً

As others have recently noted, a “bubble” does not have to be a pejorative. Collective mania can be an effective driver of massive social change for both good and ill (and whether the same could be said about the profit motive will depend on your politics). This is part of what Hoffer was getting at in The True Believer in the comparison between goal-oriented mass movements versus those which are in permanent revolution by virtue of their indeterminate aims.

Yes, the title is drawn from the techno-futurist poem, but I am reminded of something I once read in Alain de Botton’s Essays in Love about how it is risky to have a loving relationship with a regime/the State, because love can be spurned, and lovers can be prone to lashing out with intensity when they sense their counterpart is pulling away.

Tangentially, this speaks to one of my great pet peeves in the world of online writing, namely, ironic understatement, which I find nearly impossible to avoid anymore. You see this often with political commentary, where someone will describe even large-scale policy changes in very simplistic language as a manner not only of showing their own levelheadedness, but their cleverness — an inversion of expectations from the usual histrionic punditry, you see. There are advantages to straightforward expression, but as with all things, there is a balance to be struck. In this case it is between avoiding jargon and useless neologisms on the one extreme, and on the other, seeing that plain-speaking can mean a lack of specificity, which veils meaning rather than drawing it out.

You see what I mean about the understatement smothering meaning rather than heightening it.

Candidly, I laughed out loud at this clause. “Extremely good” novels! Wuthering Heights and Middlemarch are only “pretty good,” you see. An AI novel will get that elusive 5/5 stars on Goodreads, unlike the merely 4.12 Anna Karenina.

But more seriously, this is one of those lines where I realized that I had a fundamentally different perception of what the function of a novel is compared to the author. I don’t see how a novel — which allows for a unique insight into another human’s thoughts, feelings, and concerns which may be profound, delightful, confusing, horrifying, or all of the above — can, by definition, be outshone or even replicated by a machine that is producing something derivative by definition. But, as will be clear by the end, what Amodei means by “extremely good” is closer to “extremely pleasurable” or “extremely entertaining,” in which case, I suppose there is a discussion to be had about whether that can be replicated.

(The anti-tech counterargument would be that you cannot have just the “good” elements of technological development — that you cannot have vaccines and modern dentistry without the industrial/technological base which is both supporting scientific research and crushing what’s left of wild nature into dust.)

It largely takes for granted that the scientific developments in parts 1 and 2 will lead to a healthier/more robust workforce, while the AI tools’ hyperintelligence will lead to more sound decisions around economic and developmental policy. But the AI will make better policy decisions because it is hyperintelligent is getting into the territory of begging the question.

Both here and elsewhere in the piece, I noticed that I have scribbled a “why?” in the margins. Why would this superhuman AI run according to human values if the AI, in the author’s own words, will be able to do “100% of things better than humans?” Why, in its quest to cure infectious disease and all cancer, would an AI’s biological work accord to the ethical treatment of animal or human test subjects? The idea that scientific testing should be safe and humane is a concept that human scientists, for the record, have frequently resented and rejected — look at the way our scientific establishment talks about Claude Bernard, who vivisected his family dog, and whose work was so barbaric that his wife separated from him and promptly became an animal rights activist. Why would an AI take human concerns into account whatsoever? And why would an AI developer, who is convinced that an AI is superior to human beings in all tasks, take human ethics into account in the “alignment” of the AI?

This is not a new discussion, anyway — as is the case with many of our cutting-edge debates, we’ve been having it since History ended 30+ years ago. Remember the Fukuyama quote about ideological debates fading in favor of “economic calculation, the endless solving of technical problems, environmental concerns and the satisfaction of sophisticated consumer demands.”

There is also an avenue for studying these things through the lens of the “history of technics” — for example, through Lewis Mumford, who had a more optimistic approach to the potential of harmonizing human society and technological progress (and who, by virtue of this, is less cited by those who are critical of technological society than, for example, Jacques Ellul). But this will have to be done elsewhere.

I will mostly be pulling from the Shi’i Muslim tradition —specifically Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi’s The Divine Guide in Early Shi’ism — given its particularly sophisticated discussions of the person and characteristics of the mahdi. The concept has been discussed or employed at various times by those outside of the Shi’i tradition, though, I would say (in concordance with the second edition of the Encyclopedia of Islam), with less vigor and systematization.

This is part of why you see in certain examples of Muslim messianic tradition an intense interest in, for example, Jewish and Christian theology, as there is a hope for their eventual (re-)unification. I have found examples of this in those who were in Hurufi circles in particular.

It is fair to say that “individuals tend to adopt most health and consumer technologies, while technologies that are truly hampered, like nuclear power, tend to be collective political decisions.” But it is notable that military technologies — which humans do, in certain cases, band together to agree not to use — are not being discussed. I would wonder if anti-proliferation treaties would be viewed by the author as a model for restriction of military applications of AI (which are a real possibility), or if that is mere Ludditism, as well.